ODI Explains: Why Inequality Matters

Economists are keenly interested in how income is distributed

among the population. Why? It is only fair to be concerned about inequality

because, the number of poor persons in country and the average quality of life

depends on the equal or unequal distribution of income. Also, though high

levels of inequality may lead to growth as some stages of development (see

Kuznet’s hypothesis), high inequality tends to be tricky for the economy at

other times.

What then is inequality? Whenever there exists a disproportionate

distribution of total national income among households, there is inequality. In

most cases, the share of income attributed to the rich in a typical country is

far greater than the share attributed to poor segments of the population. Needless

to say that inequality of income is observable in every country of the world, developed

and developing countries alike. However, the extent of inequality differs from

country to country. For the most part, higher observable inequality in

developing countries stems from differences in the amount of income derived

from ownership of property as well as differences in earned income.

How is inequality measured? The extent of income inequality in a

society is measured by estimating its social welfare function, the outcome of

which results from the interaction of per capita income, absolute poverty and

an index of inequality. While the level of per capita income tends to have a

positive effect on welfare, both inequality and absolute poverty negatively

affect welfare. There are two common measures of income inequality based on size

distribution of income – Lorenz curve and Gini coefficient. Within the

framework of the size distribution of income, individuals or households and the

total incomes received by them are considered. It disregards locational as well

as occupational sources of incomes earned and focuses on the amount of incomes

received. The Lorenz curve and Gini coefficient are drawn out and computed

based on this personal or size distribution of income.

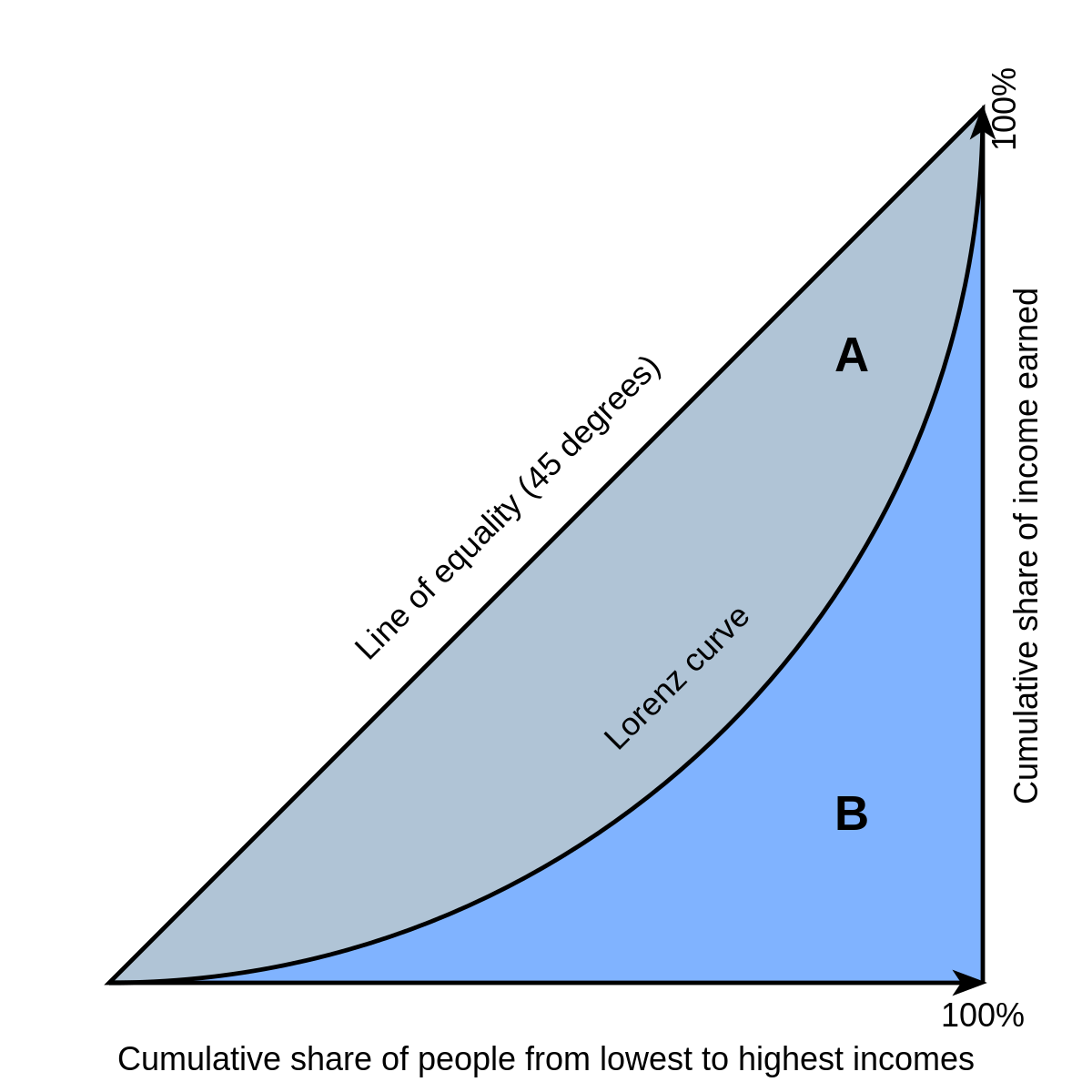

A Lorenz curve shows the actual relationship between the

percentage of income recipients and the percentage of total income received

within a given period, usually a year. The plot shows the cumulative

percentages of total income received against the cumulative percentages of

recipients, starting with the poorest household/individual. As a rule of thumb,

the greater the curvature of the Lorenz curve the greater will be the relative

degree of inequality.

There are four basic steps to the construction of a Lorenz curve.

First, we rank all individuals or households in a country by their income

level, from the poorest to the richest. Secondly, we divide all individuals or

households into five (5) groups20 per cent in each [or ten (10) groups 10 per

cent in each], then calculate income of each group and express it as percentage

of GDP. Next, we plot the shares of GDP received by these groups cumulatively

against 100 per cent of the population. Finally, the Lorenz curve emerges when

we connect all points on the chart. A linear Lorenz curve connotes an equal

distribution of income. When comparing inequality levels across countries, the

country whose Lorenz curve is farthest from the line of equality is the most

unequal in its income distribution.

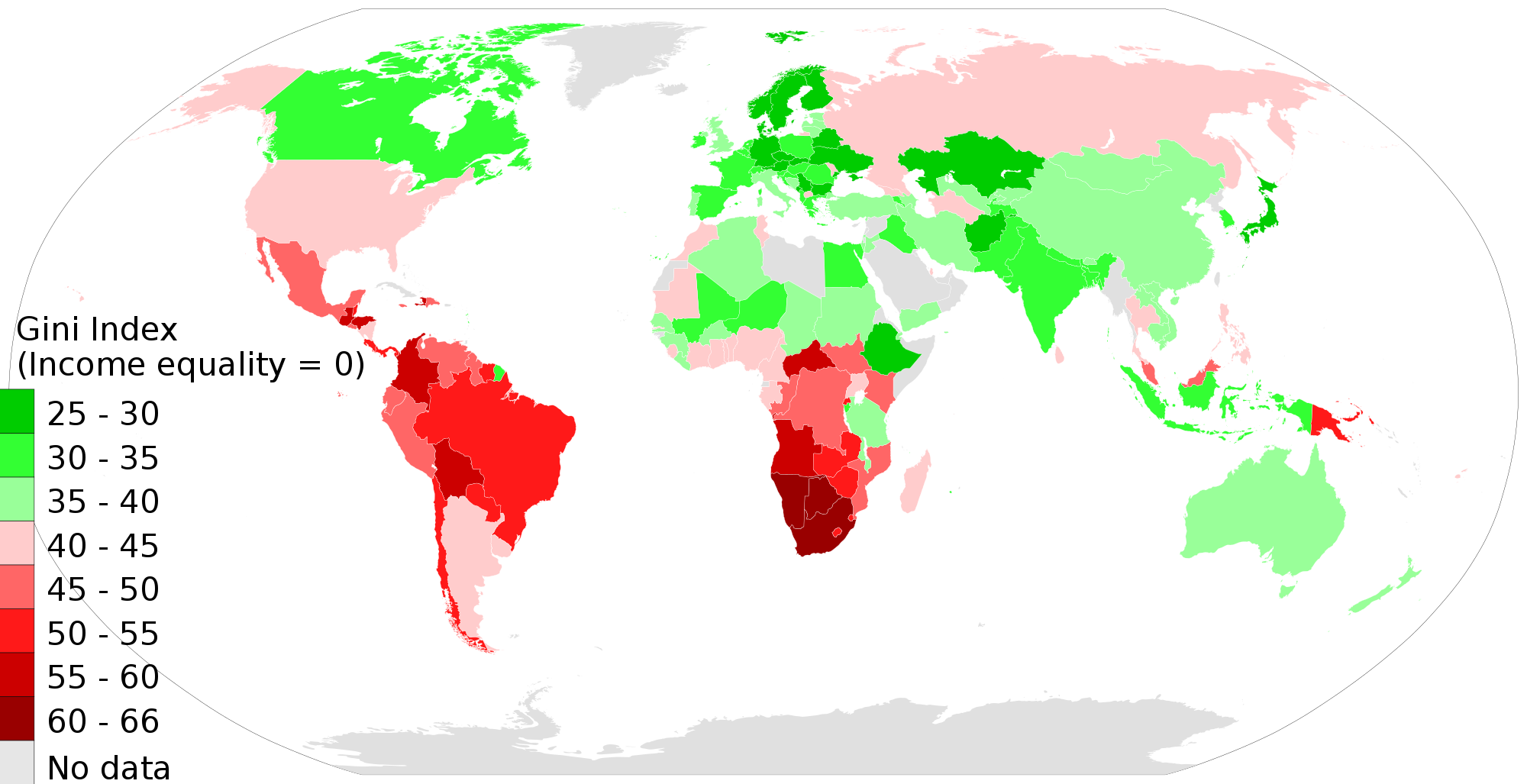

Gini coefficient is the area between a Lorenz curve and the line

of absolute equality expressed as a percentage of the triangle under the line. As

an aggregate measure of inequality, its value varies between 0 [perfect income

equality] and [perfect income inequality]. If we are set about comparing income

inequality among many countries, Gini coefficient is a more convenient

alternative than the Lorenz curve. Using the Gini coefficient, one could also

examine inequality trends in a country over a period of time.

According to Todaro and Smith, there are four (4) desirable properties of a measure of inequality, which the Gini coefficient satisfies comfortably. First is the anonymity principle. Anonymity here implies that measures of inequality should not be dependent on the nature of the individuals who are either rich or poor. It should not matter whether the individuals across the distribution are industrious or lethargic, moral or immoral. A second desirable property is scale independence. A good measure of inequality need not depend on the size of the economy being considered, for instance whether the economy under study is rich or poor on the average. Otherwise stated, a measure of inequality should be principally concerned about the dispersion and not the magnitude of income.

Thirdly, for a measure of inequality to be reliable and widely

applicable to various country contexts, it should not rely on the number of

income recipients (i.e. population independence). For instance, the economy of

India should be considered no more or less equal than the economy of Haiti

simply because India has a greater population than Haiti. Lastly, a good

measure of inequality such as the Gini coefficient is based on the transfer

principle. According to the transfer principle, assuming all other incomes are

held constant, if there are moderate transfers of income from a richer person

to poorer person, the resulting income distribution is more equal.

There is no consensus in empirical literature

on the effect of inequality of economic growth across countries. According to

the Nobel Laureate, Simon Kuznet, as a country develops inequality would first

rise then later fall. Kuznet’s inequality-growth hypothesis posits that as a

country’s industries achieve economic growth, the gap between the rich and poor

first widens and then gradually narrows. This hypothesis suggests that

increased inequality is a necessary condition for accelerating economic growth.

On the other hand, studies based on data collected by the World Bank state

otherwise, that income inequality adversely affects economic growth. The latter

results are most instructive for economies of developing countries.

There are certainly costs and benefits to inequality.

Fundamentally, a moderate level of inequality is required to promote economic

efficiency in any human society. A phenomenon of perfect equality, with no opportunity

for private profits and characterised by minimal differences in wages and

salaries, creates inefficiencies. Equality deprives individuals of the

incentives for entrepreneurship and diligent labour. For example, sheer

socialist’s wage equalization systems promote indiscipline and low initiative

among workers, poor quality of output, sluggish technical progress and economic

growth.

On the other end, high inequality has adverse effects on quality

of life. Amongst other things high inequality threatens economic stability, induces

higher incidence of poverty, limits progress in education and health, increases

social problems – crime and conflict, triggers political instability, discourages

foreign investment. Notably, countries with higher inequality are characterised

by low human capital accumulation (via education), higher fertility rates,

considerable levels of socio-political instability and poor institutions.

Can and do individuals or households move up the income

distribution? Yes, they can and they do. The more economically mobile a country

is, the better the quality of life. Economic

mobility refers to the movement of people from one part of the income

distribution to another. The higher is economic mobility, the more equal the income

distribution in the country. Wherever intergenerational economic mobility is

high, children may not likely be in the same part of income distribution with

their parents. Whole households could also move from one income group to another.

A country with a high degree of economic mobility tends to enjoy increased capacity

utilization and minimal class conflicts.

Several factors could contribute to

economic mobility in a country. Examples include: increased access to education

and health care, the nature of institutions, nature of marriages, extent of

ethnic or racial discrimination are a few such determinants of economic

mobility. On one hand, weak institutions, assortative mating practices and

presence of racial or ethnic discrimination are detrimental to economic mobility.

On the other hand, equal access to human capital development opportunities via

education and healthcare provision promotes access to economic opportunities

and enhances economic mobility.

In conclusion, it is pertinent to note these main ideas about

inequality:

• High income

does not necessarily mean equal distribution of income.

• The level of

development tends to affect the level of inequality.

• Too equal

income distribution promotes economic inefficiency.

• Too high

inequality produces socially undesirable outcomes.

• Decreasing

income inequality in developing countries is useful to accelerate economic and

human development.

• Pro-growth policies

may not inevitably lead to equal income distribution.

• Institutional

frameworks with mobility-enhancing policies provide the enabling environment

for human development.

The discussion continues…

References

Souboutina, T. P. (2004). Beyond Economic Growth: An

Introduction to Sustainable Development (2nd ed.). Washington, D.C.: The

World Bank.

Todaro, M. P., &

Smith, S. C. (2004). Economic Development (8th ed.). Delhi: Pearson

Education Singapore.

Comments